A vicious critique of advertising.

How Freud's ideas on the human condition were used to manipulate the masses.

Edward Bernays, the so-called father of public relations, used his uncle's techniques to get people to buy some of history's most vile products.

As a marketer and copywriter, I’m not supposed to talk about the dirty parts of advertising. I’m supposed to ignore the increasingly large pile of dust under the rug.

Screw that.

I’ve said it once and I’ll say it again. Marketing doesn’t have to be devious.

So today I’m talking about the sleazy, scuzzy, borderline evil parts of advertising.

And that story begins with Sigmund Freud

Believe it or not, Freud wasn’t always popular. In fact, he wasn’t very good at marketing his ideas.

Along came his American nephew, Edward Bernays, the man who would go on to be called the "Father of Public Relations."

The 2002 British documentary, Century of the Self, tells this story:

Bernays honed in on Freud's concepts around sexual anxiety and repression and used them to market Freud's book, Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis, to the mass American market.

It was an angle that worked, and it worked well. Concepts like the Oedipal Complex are still talked about today in large part to Bernays' early campaigns.

Freud, on the other hand, did not think highly of this approach. He rejected further offers for promotion as well as invitations to write paid newspaper columns. He believed that Bernays' approach was a detriment to the science of his profession.

But the damage was done.

Bernays would tell anyone and everyone about his Uncle Freud and Freud's ideas about sexual repression. He also took Freud's psychology and spun himself as a psychoanalyst to troubled corporations.

This self-styled title culminated in some of the most influential marketing campaigns of the mid-20th century

His main question was how can we use the humanity's irrational emotions, largely described by his Uncle Freud, to increase profits and sell more goods to the masses?

Bernays set up shop, calling himself a "public relations" consultant. This was the first time in history this term had been used. Bernays himself called his profession "propoganda" but knew that wartime efforts from WWI had left that word largely unpopular.

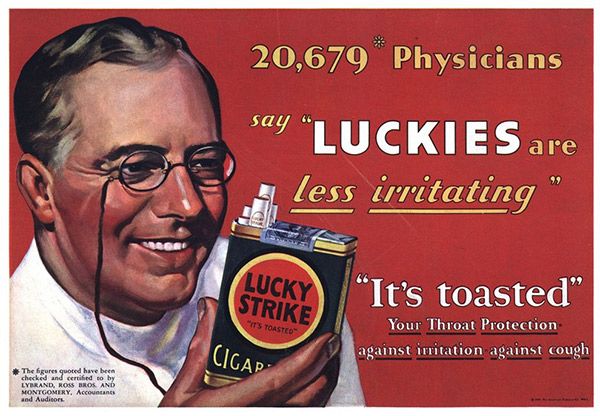

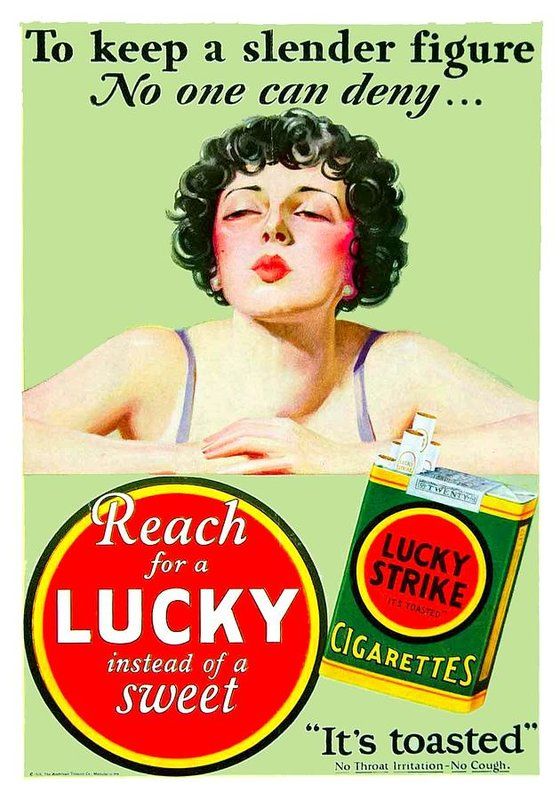

One of his earliest campaigns under this new moniker was for one of the vilest of all products.

George Helme, president of the American Tobacco Corporation, reached out to Bernays with a problem.

Cigarettes at the time were very popular amongst men.

But Helme knew that to grow sales he had to break into a new demographic. He knew that he had to get women to smoke.

Bernays reached out to A. A. Brill, one of first psychoanalysts in America. Brill said that cigarettes were phallic, that they represented raw masculinity and male sexual power. Brill said that, to women, cigarettes may be unpopular because they were a symbol of oppression and male dominance.

So Bernays did what any self-respecting psychoanalyst would do.

He sought to free women from this burden.

Torches of freedom

Brill told Bernays that if he could spin cigarettes as a challenge against male power, then women would smoke.

What came next was a media event that would manipulate the masses on a scale never seen before in advertising and marketing.

Bernays organized a group of prestigious models to smuggle in cigarettes to New York's annual Easter parade. When given the signal, they were to light up and puff away in front of all to see.

Meanwhile, Bernays informed the press that he had heard that a group of women suffragettes were planning a protest that would involve "lighting up torches of freedom."

It went off without a hitch.

The press got their juicy gossip and prize photographs and American Tobacco Corp. got their smokers.

The only one to suffer in this deal?

The American public. Especially women, whose chances to develop lung cancer would surpass that of breast cancer by 1987.

Despite the ugly outcome, we can learn a few things from this campaign

Bernays would go on to do this time and time again. You grew up with processed food, you use bar soap on a regular basis, and you've drank out of disposable cups in large part due to his campaigns.

Bernays' methods were used to start wars and win political offices.

And they're still being used today.

But marketing like this is a tool. The tool itself has no morality attached to it. A hammer can be used to build a house or smash a hand.

Let's take a look at why this "Torches of Freedom" campaign worked so well and then decide how we might use it for ourselves.

1. It took a stance

This campaign's goal was to give women access to something they didn't have before. At a time when women were fighting for their rights to vote and be seen as equals among men, torches of freedom sounded pretty damn good.

They could literally blow smoke in the face of those who stood against them.

And like most moral grey areas, this campaign (despite its ultimate outcome) may have done a lot to move that cause forward.

Here's an example of how a company with a stronger moral compass uses these same methods:

Mike DoaneWriting Inbound

Mike DoaneWriting Inbound

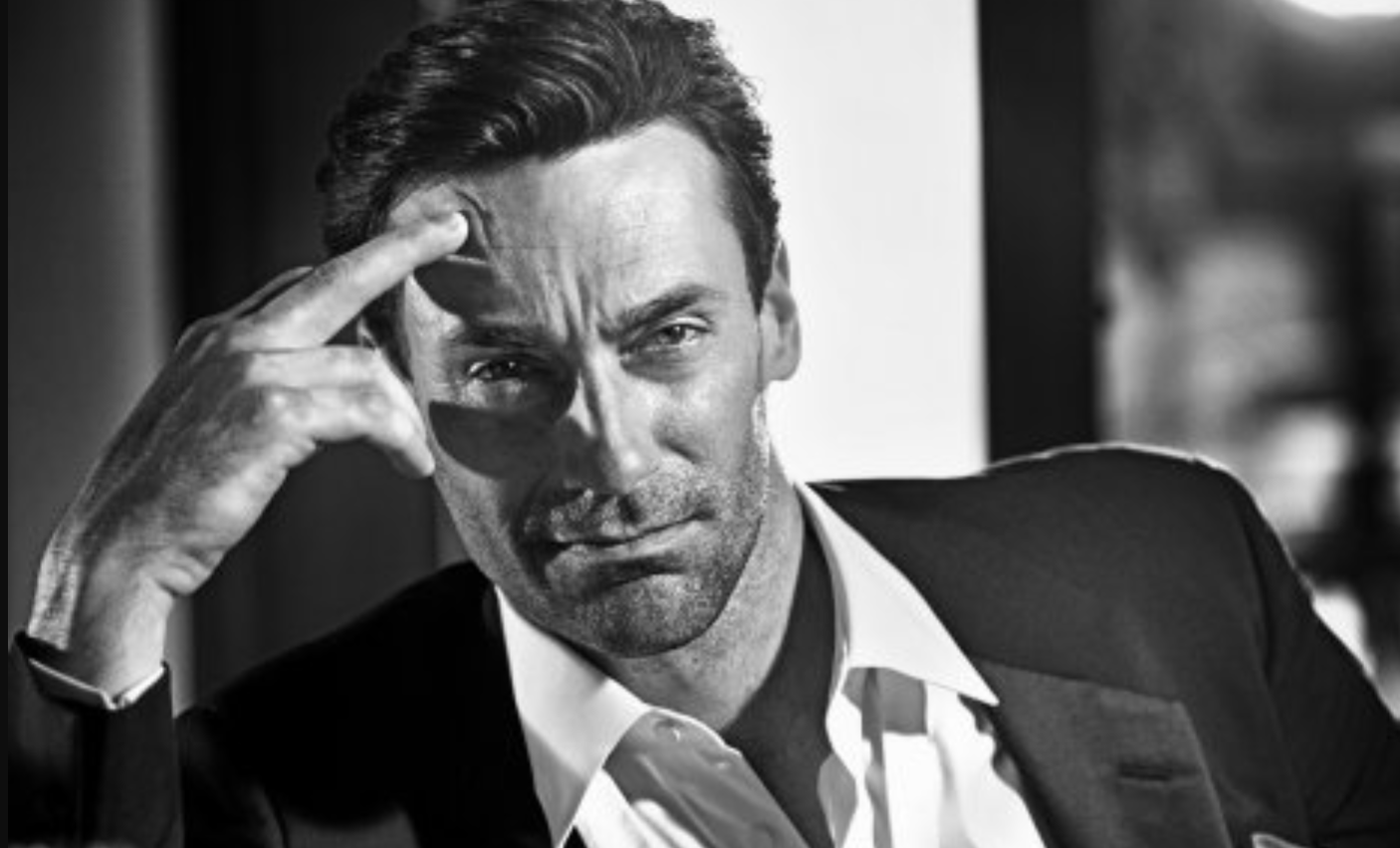

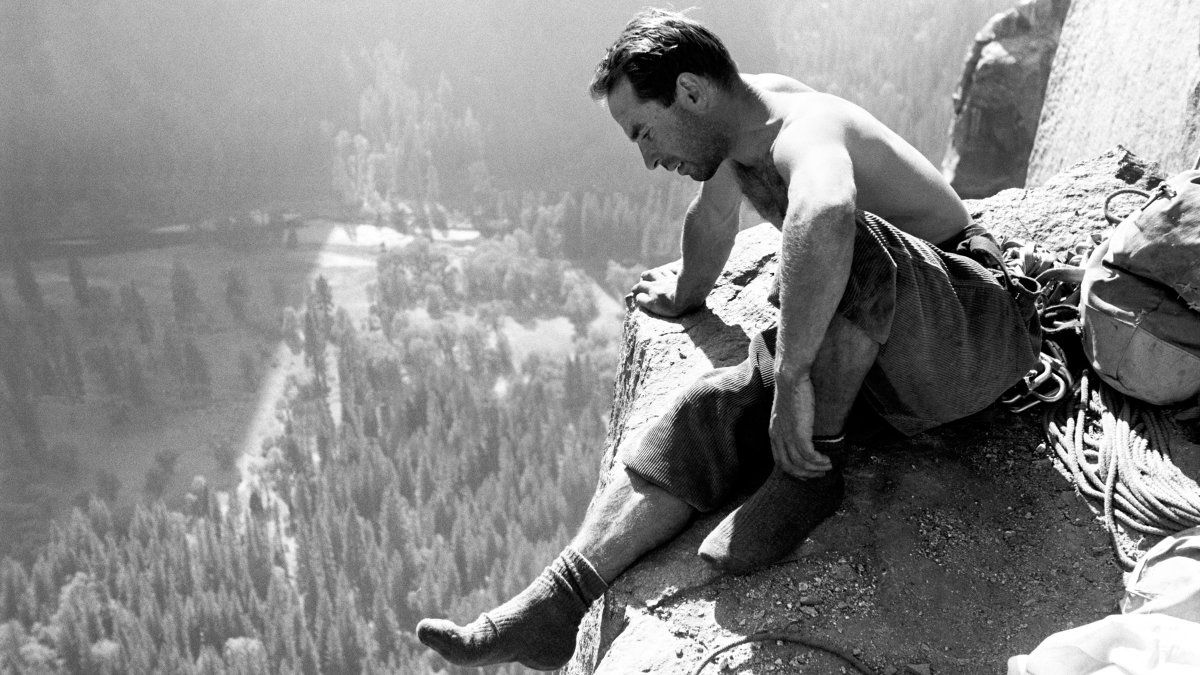

2. It showed people what they could be

Good marketing makes your ideal customer a hero. It builds them up and reflects back exactly who they want to be.

Bernay's use of prestigious models did exactly that.

Whatever the standard of beauty was at the time, these women had it. Bernays used that to manipulate the masses to buy.

I've written before on how H&M does a good job reflecting culture back to its consumers. Despite their position in the unsustainable fast-fashion industry, they work hard to uphold ethical business practices and champion diverse standards of beauty.

The difference? They're transparent about their advertising. They don't seek to package their goods as part of a Trojan Horse political movement.

You can see all of this at play in their seasonal commercials:

Mike DoaneWriting Inbound

Mike DoaneWriting Inbound

3. It used word of mouth

People love gossip. Especially the press.

Ryan Holiday's 2012 book, Trust Me, I'm Lying highlights this fact in more ways than one. The media is looking for content and will eat up anything interesting thrown their way.

Bernays knew that spinning this campaign as a political protest would perk up their ears.

Leaving a little mystery to the imagination sealed the deal.

If he had simply said these women would be lighting up cigarettes in protest, it wouldn't have nearly been as exciting.

Creating the story that they'd be protesting by lighting up these enigmatic 'torches of freedom' built up anticipation for the journalists who would be reporting on the event. The excitement they felt would not only ensure that they published information about the event, it would also prompt them to convey that excitement to their readers.

While this is a devious little way to use word of mouth, it can also be used for the benefit of your customers rather than their manipulation. Here are a few tips on that:

Mike DoaneWriting Inbound

Mike DoaneWriting Inbound

With great power comes great responsibility

And these insights are extremely powerful.

Philosopher Noam Chomsky says it may have been less Freud and more the committee of American propoganda that a young Bernays found himself on that influenced his marketing tactics, whose primary mission statement was:

The intelligent minorities can engineer consent through the use of manipulation, consent, and control to influence the public masses, and that we should do it because it is for their benefit.

Noam ChomskyDescribing Bernays' devious philosophy.

But that's a less interesting story than good ol' Uncle Freud, isn't it?

There's only one question left

Now that you have access to the marketing tools Bernays described and used, what will you do with them?

As I've mentioned, the tool itself has no morality attached to it. A hammer can be used to build a house or smash a hand.

I say, let's build more houses.

— Mike Doane

P.S. Don't walk away empty-handed

Above the Fold is a newsletter about the power of marketing. Every week I send stories just like these straight to your inbox.